Hemorrhoid Treatment: Office-Based Procedures Typically Offered to Patients

Hemorrhoid treatments are for those who have symptomatic internal hemorrhoids that are refractory to conservative medical treatments. The common objective of these therapies is to cause sloughing of excess hemorrhoidal tissue; healing and scarring then fixes the residual tissue to the underlying anorectal muscular ring. In a 2005 Cochrane review of three randomized trials, surgical hemorrhoidectomy was associated with more pain (relative risk 1.94, 95% CI 1.62-2.33) and complications (relative risk 6.32, 95% CI 1.15-34.89) than rubber band ligation.

For patients with symptomatic grade I, II, or III internal hemorrhoids refractory to conservative treatment, we recommend an office-based procedure, rather than surgical hemorrhoidectomy, as the initial intervention. Although some surgeons feel that grade III internal hemorrhoids, especially those with multiple pedicles, should be treated surgically, we recommend attempting rubber band ligation at least once. The recovery after rubber band ligation is vastly easier than after hemorrhoidectomy. If rubber band ligation fails to control symptoms adequately, surgery can then be offered.

Patients with internal hemorrhoids of any grade and additional anorectal problems, external hemorrhoids, or mixed internal/external hemorrhoids should proceed directly to surgery as those conditions are not amenable to office-based treatments.

Choice of office-based technique — Common office-based procedures for conditions performed by a gastroenterologist include rubber band ligation, sclerotherapy, infrared coagulation of internal hemorrhoids, and excision of thrombosed external hemorrhoids. The choice first depends on local availability. When local expertise is available for more than one procedure, we suggest the following:

- For healthy patients with grade I, II, or III internal hemorrhoids, we recommend rubber band ligation rather than another procedure. Compared with sclerotherapy or infrared coagulation, rubber band ligation is more effective and requires fewer treatment sessions.

- For patients who are on anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs, are immunocompromised, or have portal hypertension, we suggest sclerotherapy rather than another procedure. In such patients, rubber band ligation is contraindicated due to the high risk of delayed bleeding, and sclerotherapy is better studied than infrared coagulation in the literature for this group of patients.

- Acutely thrombosed external hemorrhoids can be treated by office-based excision if the patient presents within the first three days of symptoms. The symptoms usually begin to subside after three days and typically dissipate in 7 to 10 days. Extensive or bleeding thrombosed external hemorrhoids may require surgical excision in the operating room.

- Grade IV internal hemorrhoids require definitive surgical treatment. Office-based procedures are ineffective and should not be attempted.

- Patients should be informed before the procedure that office-based procedures do not address any external component (eg, skin tag) of the hemorrhoid.

Techniques

Rubber band ligation — Rubber band ligation is the most commonly used technique for the treatment of symptomatic bleeding internal hemorrhoids. This technique is effective, inexpensive, easy to perform by a gastroenterologist and only rarely causes serious complications.

Patients with grade II or III internal hemorrhoids are the best candidates for rubber band ligation. External tags and external hemorrhoids are not to be treated with this technique, as it would cause excruciating pain. Banding procedures are typically contraindicated in patients with coagulopathies and those on anticoagulation (eg, warfarin , apixaban [Eliquis], dabigatran [Pradaxa], rivaroxaban [Xarelto]) or antiplatelet (eg, clopidogrel [Plavix]) medications, and patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension, because of the risk of significant delayed hemorrhage. In the authors’ experience, patients on aspirin therapy can safely undergo rubber band ligation, with a low risk of bleeding. Banding is relatively contraindicated in immunocompromised patients (eg, chemotherapy administration, HIV/AIDS) because of risks of infection and sepsis.

When performed properly, this procedure does not require any anesthesia (local or intravenous). Usually, only one hemorrhoidal column should be treated at a time to minimize excessive tissue necrosis. However, if the patient tolerates the procedure with only minimal discomfort, then several hemorrhoids can be banded during the same session. As many as three bands in a single column may be safely performed. If multiple sessions are needed, then repeat banding procedures can be performed in three- to four-week intervals to allow any swelling and ulcerations to subside. Many patients complain of anal or rectal “tightness” after the procedure.

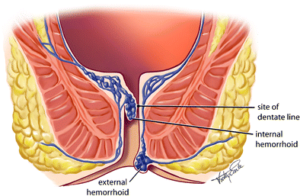

Patients are placed in the semi-inverted jackknife or left lateral position. The procedure is performed through the anoscope, and small rubber band rings are placed onto the internal hemorrhoids traditionally using a forceps, but other methods have been developed. When a forceps ligator is used to apply the bands, an assistant is required to stabilize the anoscope. Once the involved hemorrhoid is identified through an anoscope, the rubber ring ligating drum with two rubber rings is placed into the anal canal. The largest internal hemorrhoid should be treated first. The internal hemorrhoid is grasped with forceps, and the excess tissue is pulled toward the tip or drum of the handheld ligator gun apparatus while the trigger causes the release of the rubber band. The rubber rings are then advanced down to the neck of the hemorrhoid. The key technical point is to ensure the bands are placed at least 5 mm above the dentate line to avoid placement onto somatically innervated tissue. Severe pain will result from misapplication of the band below the dentate line or from associated spasm. Thus, prior to rubber band release, the patient should be questioned about the presence of pain, which may indicate the need to select a point more proximal in the anal canal. If a patient experiences intense or excruciating pain as the rubber band is placed, then the band should be removed immediately by cutting the rubber band.

Other application techniques have been described. Each uses the same principles as the traditional forceps approach described above.

- Endoscopic suction ligator – An alternative technique involves suction of the symptomatic hemorrhoid into the ligating drum, which is attached to an endoscope. The ring is deployed through a trigger passed through the biopsy channel of the endoscope. This approach may allow for adequate ligation with fewer treatment sessions. A single-handed nonendoscopic ligating device has also been used successfully and is less expensive than the endoscopic device.

- Wall suction ligator – Another technique uses a vacuum suction band ligator. The application of the rubber band using wall suction can be performed in fewer sessions compared with the standard forceps technique (1.2 versus 2 sessions). The principles are the same, but the rubber band ligator is attached to wall suction. The operator places the drum with the rubber band against the hemorrhoid. Suction pulls the hemorrhoid into the drum, and the rubber band is deployed. The technical advantage is that the operator can hold the ligator and apply the band with one hand and hold the anoscope with the other unassisted.

Successful ligation results in thrombosis of the hemorrhoid and the development of localized submucosal scarring. The banded hemorrhoidal tissues immediately become ischemic and then necrotic in the next three to five days, forming an ulcerated tissue bed. Complete healing occurs several weeks later.

One of the largest series to describe long-term outcomes of rubber band ligation included 805 patients who underwent 2114 ligations (median of two ligations in each patient). Excluding 104 patients who were lost to follow-up, treatment was considered successful in 71 percent (80 percent when considering patients who underwent repeated treatment after initial failure). Success rates were similar for all degrees of hemorrhoids. A higher failure rate was observed in patients who required placement of four or more bands.

In a meta-analysis of 12 trials, bleeding stopped after rubber band ligation in up to 90 percent of patients; 78 to 84 percent of those with grade III (prolapsing) hemorrhoids reported symptomatic improvement, and only 50 percent of patients with grade IV hemorrhoids had improvement. The most common complications are bleeding and pain (8 to 80 percent). However, the success rate often decreases with longer follow-up (eg, 40 to 50 percent at one year.

In a meta-analysis of 18 trials, rubber band ligation was more effective than injection sclerotherapy or infrared coagulation for the treatment of grade I, II, and III hemorrhoids, requiring fewer treatment sessions. The risk of complications and pain tended to be greater for rubber band ligation compared with other techniques. Compared with surgery, rubber band ligation had more recurrent symptoms but was associated with fewer complications and pain.

Following rubber band ligation, the most frequent complication is pain, which occurs in approximately 8 percent. Other complications include:

- Delayed hemorrhage – Delayed hemorrhage can occur when the rubber band dislodges, typically two to four days after application or with ulceration and mucosal sloughing, which can occur five to seven days after the procedure. Bleeding can be significant in patients with coagulation abnormalities.

- Hemorrhoidal thrombosis – Hemorrhoids distal to the treated hemorrhoid can thrombose, leading to pain or a palpable mass.

- Localized infection – Localized infection or abscess can occur at the site of band ligation. Persistent pain, fever, or foul-smelling rectal drainage may signal the onset of infection. Surgical drainage may be required.

- Sepsis – Fulminant sepsis after hemorrhoid ligation is rare but has been reported.

- Urinary retention.

Sclerotherapy — Injectable sclerosant solutions can also be used to treat symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. The most common solution used is phenol (5%) in vegetable oil, although other sclerosants such as sodium morrhuate , quinine , urea hydrochloride, sodium tetradecyl sulfate (Sotradecol), and hypertonic saline have all been used. The sclerosant causes an intense inflammatory reaction, destroying redundant submucosal tissue associated with hemorrhoidal prolapse.

As with rubber band ligation, sclerotherapy does not require anesthesia (local or intravenous). Patients are placed in the semi-inverted jackknife or left lateral position, and the procedure is performed through the anoscope. The internal hemorrhoids targeted for treatment are located and injected with 1 to 3 cc of the sclerosant material into the submucosa plane using a long intravenous 21 gauge needle or a spinal needle. A wheal should be raised with the solution. If the injection is too superficial, the area will become tense and blanched, and the injection should stop immediately to minimize risk of mucosal necrosis.

This approach can be used to treat grade I and II bleeding internal hemorrhoids with reported success rates of 75 to 89 percent, which has more recurrences than rubber band ligation. In a meta-analysis of five trials, sclerotherapy resolved 90 to 100 percent of grade II hemorrhoids; 36 to 49 percent of patients reported postprocedural pain. Bleeding is rare after sclerotherapy .

Thus, sclerotherapy is especially beneficial to patients with an elevated bleeding risk (eg, those on anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs and those with portal hypertension) due to a lack of eschar formation and patients who are immunocompromised due to a lower risk of anorectal sepsis compared with rubber band ligation or hemorrhoidectomy.

Complications of sclerotherapy are also uncommon, with the most frequent being minor discomfort or bleeding with the injection. Rectourethral fistulas, rectal perforations, and necrosing fasciitis are rare complications but can occur with misplaced injections into nonhemorrhoidal tissues or with systemic injections into the vasculature.

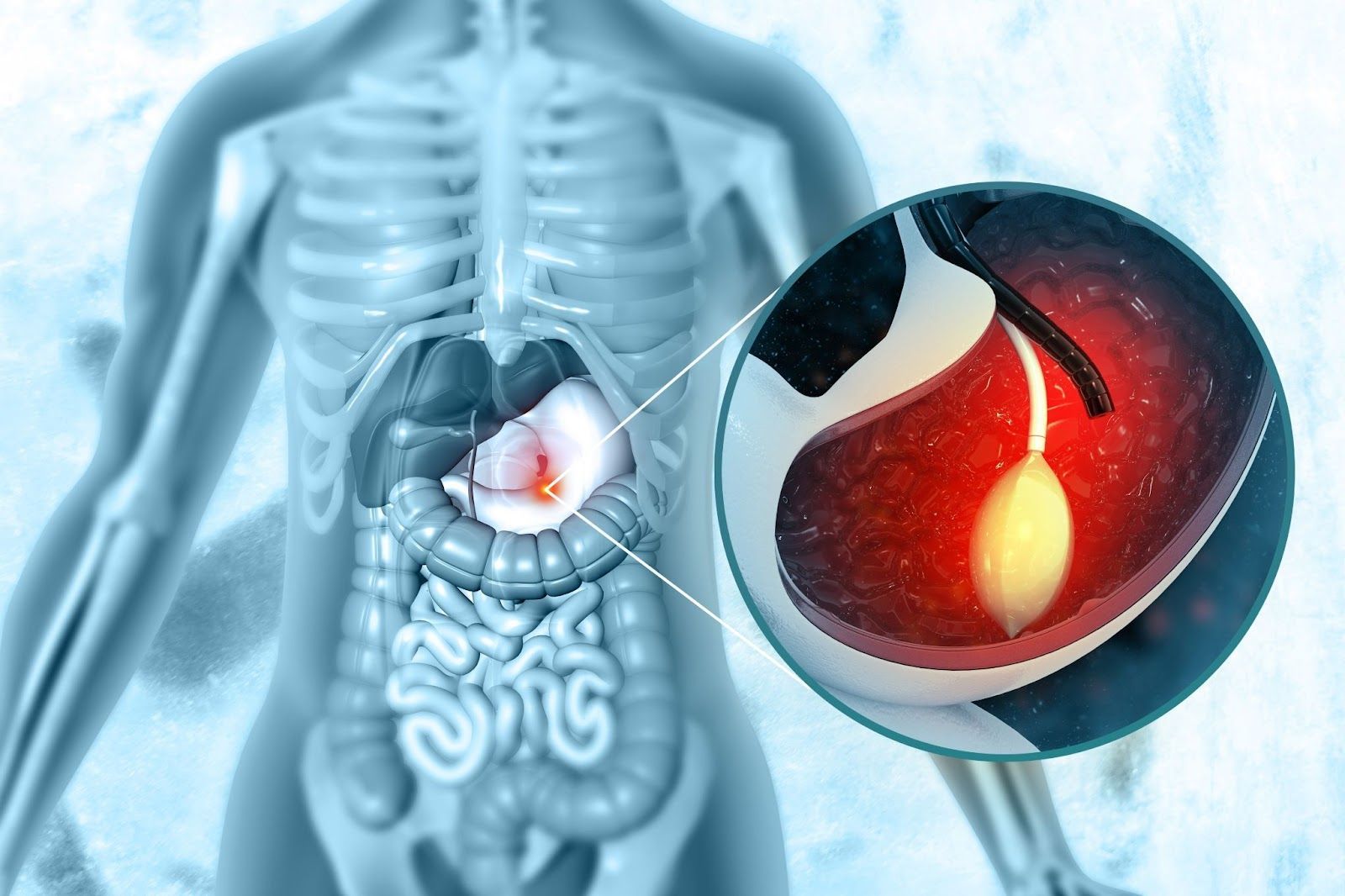

Infrared coagulation — Infrared coagulation involves the direct application of infrared light waves to the hemorrhoidal tissues. Patients with grade I or II bleeding internal hemorrhoids are candidates for this procedure.

Infrared coagulation is sometimes erroneously referred to as laser therapy. Infrared light waves are converted into heat, which results in protein necrosis within the hemorrhoid. This is seen as a white, blanching effect to the mucosa approximately 3 mm wide by 3 mm deep. Over a period of one to two weeks, the white, discolored mucosa changes into a dark scab and eventually leads to a puckered or ablated area, causing retraction of the redundant hemorrhoid mucosa.

The patient is positioned in the semi-inverted jackknife or left lateral position, and anoscopy is performed. The tip of the infrared coagulation applicator or probe is applied to the base of the internal hemorrhoid for two seconds, with three to five applications per hemorrhoid.

In a meta-analysis of four trials, 78, 51 and 22 percent of patients with grade I, II and III hemorrhoids reported improvement after infrared coagulation therapy. Postoperative pain and bleeding occurred in 15 to 100 percent and 15 to 44 percent of patients, respectively. The recurrence rate was 13 percent at three months.

Compared with rubber band ligation, infrared coagulation is associated with more recurrences but fewer complications and causes less discomfort immediately after the procedure.

Others — Other techniques involve the application of monopolar cautery (electrotherapy), bipolar diathermy (Bicap, HET bipolar system), laser photocoagulation, or cryosurgery to cause coagulation and necrosis, which leads to fibrosis in the submucosal layer. They are generally effective for grade I to II internal hemorrhoids, and each has its advocates.

Electrotherapy uses a probe to deliver an electric current to the base of the hemorrhoid above the dentate line to cause the hemorrhoid to shrink. It has been used to treat grade I to III internal hemorrhoids. A low-amplitude direct electric current setting (between 8 and 16 mA) can be used in an outpatient setting but often requires repeat procedures; the use of higher amplitudes (up to 30 mA) requires anesthesia.

The HET bipolar system uses bipolar energy to treat symptomatic grade I and II internal hemorrhoids refractory to medical therapy. Limited data have shown it to be safe, effective, and painless, and it may be an alternative to rubber band ligation for large internal hemorrhoids and those close to the dentate line.

Hemorrhoidectomy using the neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) or carbon dioxide laser has been described. However, these approaches do not appear to offer a significant advantage to other approaches, and the required equipment is expensive. Furthermore, serious complications have been described.

Cryosurgery is the application of special probes cooled with liquid nitrogen, which causes freezing, necrosis, and subsequent fixation of the hemorrhoidal cushion. Cryosurgery may be associated with a higher rate of complication and less patient satisfaction.

Postprocedure care and follow-up — Following office-based procedures, patients are instructed to avoid constipation by using stool softeners and consuming a diet high in fiber and water. If the patient experiences anal or rectal pain or discomfort, warm sitz baths and oral pain medication are advised. The postprocedure instructions are similar to those given following surgical hemorrhoidectomy.

A rare but life-threatening complication with all office-based procedures is perineal sepsis, which is usually heralded by a triad of severe pain, urinary retention, and fever. Any patient with these symptoms should have follow-up immediately for further evaluation.

The prevalence of rectal pathology among patients who present with symptomatic hemorrhoid disease is unknown. Following resolution of symptoms, it is reasonable to suggest a sigmoidoscopy if this has not been previously performed. A colonoscopy can be considered in patients with risk factors for colorectal cancer or in those older than 50 years of age, in whom it serves the added purpose of screening for colorectal cancer.

Source : Uptodate ®

The post Hemorrhoid Treatment: Office-Based Procedures Typically Offered to Patients appeared first on Gastro SB.